"Manufacturing Consent": The Media as a Propaganda Model

By Beneath The Olive Tree | 5-11-2024

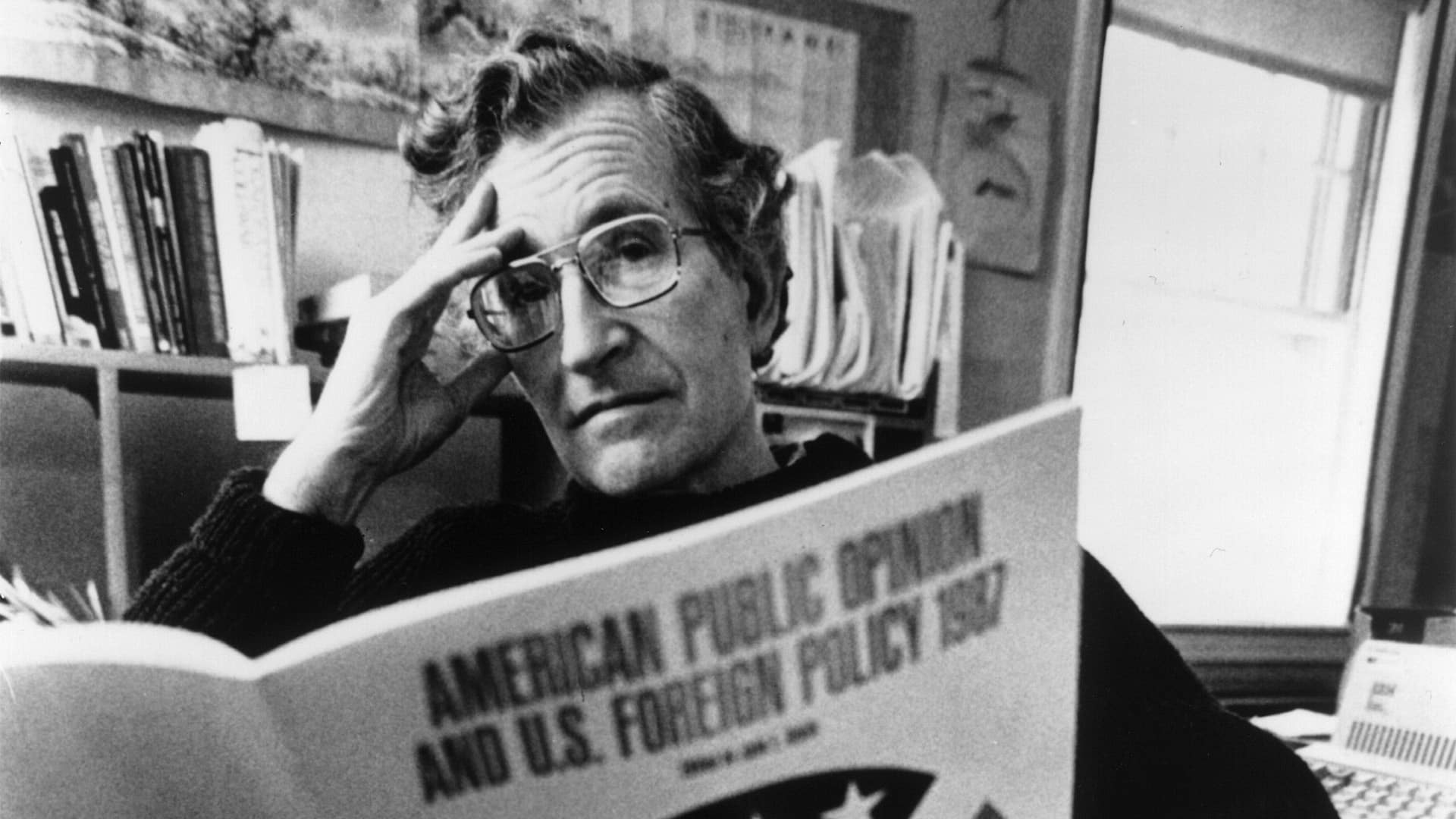

The mainstream tends to be what was once called a herd of independent minds marching in support of State power. - Noam Chomsky

In analyzing the mainstream media’s alignment with government narratives on foreign policy issues, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media by Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman provides a critical framework. Published in 1988, Manufacturing Consent argues that mainstream media in capitalist societies functions less as an independent check on government power and more as a vehicle for advancing elite interests, especially in matters of foreign policy. Herman and Chomsky outline a “propaganda model” of media, which explains how economic and political pressures drive media outlets to reflect government perspectives, selectively covering issues in a way that benefits powerful interests.

The Propaganda Model and Its Components

The propaganda model introduced in Manufacturing Consent identifies five key filters that influence media content and determine what stories are told and how. These filters shape coverage by filtering out information that may challenge the status quo or threaten elite interests, while amplifying narratives that support them.

- Ownership: Most mainstream media outlets are owned by large corporations with financial ties to other powerful industries and government bodies. This ownership structure discourages content that could harm corporate profits or damage relationships with influential figures. In conflicts like the Iraq War and the Israel-Palestine conflict, media corporations may avoid questioning government narratives to protect their own financial and political interests.

- Advertising: Media outlets rely heavily on advertising revenue, which can influence content by discouraging stories that may alienate advertisers or their target audiences. This reliance leads to a conservative approach, where coverage is shaped to be non-controversial to appeal to large advertisers. For instance, during the Iraq War, media outlets’ uncritical repetition of WMD claims helped maintain a narrative that was widely palatable to audiences and advertisers alike, avoiding controversy.

- Sourcing: To produce news efficiently and with authority, media outlets rely on government and corporate sources. Official sources are seen as credible, providing information “from the top,” which often goes unchallenged. In matters of foreign policy, this reliance on official sources limits the range of perspectives available, as dissenting voices and independent reports are often ignored. In the Afghanistan War, for instance, heavy reliance on government and military sources led to coverage that largely reflected the official narrative of “fighting terror,” downplaying the impacts of occupation on Afghan civilians.

- Flak: This term refers to negative responses to media content, such as complaints, legal threats, or political pressure, which can discourage outlets from running stories that might provoke backlash. Journalists who question government actions or report critically on foreign policy may face accusations of being “unpatriotic” or “biased,” which pressures media outlets to conform to safer, government-approved narratives. This was particularly evident during the Vietnam War, when early critical reports faced severe backlash, leading to a cautious, pro-government stance in many outlets.

- Anti-Communism and Ideology (or Anti-Terrorism, in the Post-9/11 Context): The propaganda model argues that ideological filters like anti-communism (during the Cold War) or anti-terrorism (in the post-9/11 era) shape media narratives to justify government actions abroad. For instance, in the early years of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, media coverage largely embraced the “War on Terror” framework, which cast U.S. interventions as morally justified responses to a global threat. This ideological alignment discouraged deep scrutiny of the U.S. military’s actions and often framed local resistance as “terrorism” rather than as a reaction to foreign occupation.

These filters, according to Herman and Chomsky, work together to create an environment in which mainstream media, rather than challenging government narratives, tends to reinforce and normalize them. By selectively covering stories, emphasizing certain sources, and adhering to ideological expectations, the media effectively “manufactures consent” among the public, generating passive support for government policies—even when these policies have significant ethical, financial, and human costs.

Member discussion